Japanese Architecture(summary)

Before i pass through more specific information about Japanese Architecture i ought to post a few general information about it’s history.

By Wikipedia!

Japanese architecture (日本建築 Nihon kenchiku?) has a long history as any other aspect of Japanese culture. Originally heavily influenced by Chinese architecture from the Tang Dynasty, as well as by Korea of the same period (which reflected Chinese Buddhist style architecture), it has also developed many unique differences and aspects indigenous to Japan as a result of dynamic changes throughout its long history.

Prehistoric period

Reconstructed pit dwelling houses in Yoshinogari,Saga Prefecture, 2nd or 3rd century

Reconstructed dwellings inYoshinogari

Reconstructed raised-floor building in Yoshinogari

The prehistoric period includes the Jomon and Yayoi cultures and other cultures before the Jomon and Yayoi cultures. There are no extant examples of prehistoric architecture, and the oldest Japanese texts, such as Kojiki and Nihonshoki hardly mention architecture at all. Excavations and researches show these houses had thatched roofs and dirt floors. Houses in areas of high temperature and humidity had wooden floors. With the spread of rice cultivation from China, communities became increasingly larger and more complex, and large scale buildings for the local ruling family or rice storage houses are seen in Sannai-Maruyama site (before 2nd century BC) in Aomori or Yoshinogari site in Saga (before 3rd century BC).

After the 3rd century, a centralized administrative system was developed and many keyhole-shaped Kofun were built in Osaka and Nara for the aristocracy. Among many examples in Nara and Osaka, the most notable is Daisen-kofun, designated as the tomb of Emperor Nintoku. This kofun is approximately 486 by 305 m, rising to a height of 35 m.

Asuka and Nara architecture

The earliest structures still extant in Japan, and the oldest surviving wooden buildings in the world are found at the Hōryū-ji to the southwest of Nara. They serve as the core examples of architecture in Asuka period. First built in the early 7th century as the private temple of Crown Prince Shotoku consists of 41 independent buildings; the most important ones, the main worship hall, or Kondo (Golden Hall), and Goju-no-to (Five-story Pagoda), stand in the center of an open area surrounded by a roofed cloister. The Kondo, in the style of Chinese worshiphalls, is a two-story structure of post-and-beam construction, capped by an irimoya, or hipped-gabled roof of ceramic tiles.

Temple building in the 8th century was focused around the Tōdaiji in Nara. Constructed as the headquarters for a network of temples in each of the provinces, the Tōdaiji is the most ambitious religious complex erected in the early centuries of Buddhist worship in Japan. Appropriately, the 16.2-m (53-ft) Buddha (completed in 752) enshrined in the main hall, orDaibutsuden, is a Rushana Buddha, the figure that represents the essence of Buddhahood, just as the Tōdai-ji represented the center for imperially sponsored Buddhism and its dissemination throughout Japan. Only a few fragments of the original statue survive, and the present hall and central Buddha are reconstructions from the Edo period. Clustered around the Daibutsuden on a gently sloping hillside are a number of secondary halls: the Hokkedo (Lotus Sutra Hall), with its principal image, the Fukukenjaku Kannon (the most popular bodhisattva), crafted of dry lacquer (cloth dipped in lacquer and shaped over a wooden armature); the Kaidanin (Ordination Hall) with its magnificent clay statues of the Four Guardian Kings; and the storehouse, called the Shosoin. This last structure is of great importance as an art-historical cache, because in it are stored the utensils that were used in the temple’s dedication ceremony in 752, the eye-opening ritual for the Rushana image, as well as government documents and many secular objects owned by the imperial family.

Pagoda at Yakushi-ji, Nara, Nara Orignally built in 730 Kondo and pagoda at Hōryū-ji, Ikaruga, Nara

Kondo and pagoda at Hōryū-ji, Ikaruga, NaraBuilt in 7th century

Shōsōin at Todaiji, Nara, Nara

Shōsōin at Todaiji, Nara, NaraBuilt in 8th century

Hokkedō at Tōdai-ji, Nara, Nara

Hokkedō at Tōdai-ji, Nara, NaraFounded in 743

Heian period

In reaction to the growing wealth and power of organized Buddhism in Nara, the priest Kūkai (best known by his posthumous title Kōbō Daishi, 774-835) journeyed to China to studyShingon, a form of Vajrayana Buddhism, which he introduced into Japan in 806. At the core of Shingon worship are the various mandalas, diagrams of the spiritual universe which influenced temple design. Japanese Buddhist architecture also adopted the stupa in its Chinese form of pagoda.

The temples erected for this new sect were built in the mountains, far away from the court and the laity in the capital. The irregular topography of these sites forced Japanese architects to rethink the problems of temple construction, and in so doing to choose more indigenous elements of design. Cypress-bark roofs replaced those of ceramic tile, wood planks were used instead of earthen floors, and a separate worship area for the laity was added in front of the main sanctuary.

In the Fujiwara period, Pure Land Buddhism, which offered easy salvation through belief in Amida (the Buddha of the Western Paradise), became popular. Concurrently, the Kyoto nobility developed a society devoted to elegant aesthetic pursuits. So secure and beautiful was their world that they could not conceive of Paradise as being much different. The Amida hall, blending the secular with the religious, houses one or more Buddha images within a structure resembling the mansions of the nobility.

The Hōō-dō (Phoenix Hall, completed 1053) of the Byōdō-in, a temple in Uji to the southeast of Kyoto, is the exemplar of Fujiwara Amida halls. It consists of a main rectangular structure flanked by two L-shaped wing corridors and a tail corridor, set at the edge of a large artificial pond. Inside, a single golden image of Amida (circa 1053) is installed on a high platform. The Amida sculpture was executed by Jocho, who used a new canon of proportions and a new technique (yosegi), in which multiple pieces of wood are carved out like shells and joined from the inside. Applied to the walls of the hall are small relief carvings of celestials, the host believed to have accompanied Amida when he descended from the Western Paradise to gather the souls of believers at the moment of death and transport them in lotus blossoms to Paradise. Raigo (Descent of the Amida Buddha) paintings on the wooden doors of the Ho-o-do are an early example of Yamato-e, Japanese-style painting, because they contain representations of the scenery around Kyoto.

Phoenix Hall at Byodoin, Uji, Kyoto

Phoenix Hall at Byodoin, Uji, Kyoto

Built in 1053

Ujigami Shrine, Uji, Kyoto

Ujigami Shrine, Uji, Kyoto

Built in 1060

Pagoda of Ichijō-ji, Kasai, Hyōgo

Pagoda of Ichijō-ji, Kasai, Hyōgo

Built in 1171

Nageiredō of Sanbutsuji, Misasa, Tottori

Nageiredō of Sanbutsuji, Misasa, Tottori

Kamakura and Muromachi period

Jōdodō of Jōdo-ji, Ono, Hyōgo

Jōdodō of Jōdo-ji, Ono, Hyōgo

Built in 1194

Nandaimon of Tōdai-ji, Nara, Nara

Built in 1199

Sanjūsangen-dō, Kyoto

Built in 1266

Pagoda of Jigen-in, Izumisano, Osaka

Built in 1271

Butsuden of Kōzan-ji, Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi

Built in 1320

Fudō-in Iwayadō, Wakasa, Tottori

Fudō-in Iwayadō, Wakasa, Tottori

Built in 14th century

Ginkakuji, Kyoto

Ginkakuji, Kyoto

Built in 15th century

Daitō of Negoro-ji in Iwade, Wakayama

Daitō of Negoro-ji in Iwade, Wakayama

Completed in 1547

During the Kamakura period (1185–1333) and Muromachi period (1336-1573), Japanese architecture made technological advances that somewhat diverged from and Chinese counterparts.(Daibutsu-Style and Zen-Style)[5][6][7] In response to native requirements such as earthquake resistance and shelter against heavy rainfall and the summer heat and sun, the master carpenters of this time responded with a unique type of architecture.[8] Unfortunately, the heavy reliance on wood as the primary building material has meant that fires destroyed many of the original structures but some do survive such as Jōdo-ji in Ono (Daibutsu-Style) and Kōzan-ji in Shimonoseki (Zen-Style).

After the Kamakura period, Japanese political power was dominated by the armed Samurai, such as Seiwa Genji. Their simple and sturdy ideas affected the architecture style, and many samurai houses are a mixture of shinden-zukuri and turrets or trenches.

In the Genpei War (1180-1185), many traditional buildings in Nara and Kyoto were damaged. For example, Kofukuji and Todaiji were burned down by Taira no Shigehira of the Taira clan in 1180. Many of these temples and shrines were rebuilt in the Kamakura period by the Kamakura shogunate to consolidate the shogun‘s authority. This program was carried out in such an extensive scale that many of the temples and shrines built after the Kamakura period were influenced by this architectural style.

Especially, remarkable event in Muromachi period, another major development of the period was the tea ceremony and the tea house in which it was held. The purpose of the ceremony is to spend time with friends who enjoy the arts, to cleanse the mind of the concerns of daily life, and to receive a bowl of tea served in a gracious and tasteful manner. Zen was the basic philosophy. The rustic style of the rural cottage was adopted for the tea house, emphasizing such natural materials as bark-covered logs and woven straw. In addition, a traditional Japanese style culture such as tatami, shōji, and fusuma was stylized in Muromachi period.

Azuchi-Momoyama period

Himeji Castle in Himeji, Hyōgo,

Himeji Castle in Himeji, Hyōgo,

Completed in 1618

Matsumoto Castle in Matsumoto, Nagano,

Matsumoto Castle in Matsumoto, Nagano,

Completed in 1600.

Dry stone walls of Kumamoto Castle,

Dry stone walls of Kumamoto Castle,

Completed in 1600.

Ninomaru Palace within Nijo Castle, Kyoto

Ninomaru Palace within Nijo Castle, Kyoto

Two new forms of architecture were developed in response to the militaristic climate of the times: the castle, a defensive structure built to house a feudal lord and his soldiers in times of trouble; and the shoin, a reception hall and private study area designed to reflect the relationships of lord and vassal within a feudal society. Himeji Castle (built in its present form 1609), popularly known as White Heron Castle, with its gracefully curving roofs and its complex of three subsidiary towers around the main tenshu (or keep), is one of the most beautiful structures of the Momoyama period. The Ohiroma of Nijo Castle (17th century) in Kyoto is one of the classic examples of the shoin, with its tokonoma (alcove), shoin window (overlooking a carefully landscaped garden), and clearly differentiated areas for the Tokugawa lords and their vassals.

Edo period

Hirosaki Castle in Hirosaki, Aomori

Hirosaki Castle in Hirosaki, Aomori

Completed in 1611

Yomeimon of Toshogu, Nikko, Tochigi

Yomeimon of Toshogu, Nikko, Tochigi

Inside the Shokintei at Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto

Inside the Shokintei at Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto

Built in 17th century

Three halls of Engyō-ji in Himeji, Hyōgo, Completed in 18th century

Three halls of Engyō-ji in Himeji, Hyōgo, Completed in 18th century

Katsura Detached Palace, built in imitation of Prince Genji‘s palace, contains a cluster of shoin buildings that combine elements of classic Japanese architecture with innovative restatements. The whole complex is surrounded by a beautiful garden with paths for walking 😉

The city of Edo was repeatedly struck by fires, leading to the development of a simplified architecture that allowed for easy reconstruction. Because fires were most likely to spread during the dry winters, lumber was stockpiled in nearby towns prior to their onset. Once a fire that had broken out was extinguished, the lumber was sent to Edo, allowing many rows of houses to be quickly rebuilt. Due to the shogun’s policy of sankin kotai (“rotation of services”), the daimyo constructed large houses and parks for their guests’ (as well as their own) enjoyment. Kōrakuen is a park from that period that still exists and is open to the public for afternoon walks.

Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods

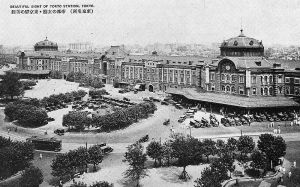

Tokyo Station, Built in 1914

Tokyo Station, Built in 1914

National Diet Building in Tokyo, Built in 1936

National Diet Building in Tokyo, Built in 1936

Kyoto National Museum in Kyoto, Built in 1895

Kyoto National Museum in Kyoto, Built in 1895

Old Hyogo Prefectural Office Building in Kobe, Hyōgo, Built in 1902

Old Hyogo Prefectural Office Building in Kobe, Hyōgo, Built in 1902

In the years after 1867, when Emperor Meiji ascended the throne, Japan was once again invaded by new and alien forms of culture. By the early 20th century, European art forms were well introduced and their marriage produced notable buildings like the Tokyo Train Station and the National Diet Building that still exist today.

In early 1920s, modernists and expressionists emerged and began to form their own groups. Kunio Maekawa and Junzo Sakakura joined Le Corbusier‘s studio in France, came back to Japan in early 1930s, and designed several buildings. Influence of modernism spread to many company and government buildings. In 1933 Bruno Taut fled to Japan, and his positive opinion of Japanese architecture (especially Katsura Imperial Villa) encouraged Japanese modernists.

Modern architecture

Skyscrapers of Shinjuku, Tokyo

National Gymnasium in Yoyogi Park, Tokyo, Design by Kenzo Tange

Yokohama Landmark Tower in Minato Mirai 21, Yokohama

JR Central Towers in Nagoya, Aichi, Built in 1999

JR Central Towers in Nagoya, Aichi, Built in 1999

Kyoto Station, Kyoto, Built in 1997, Design by Hiroshi Hara

Awaji Yumebutai in Awaji, Hyōgo, Built in 2000, Design by Tadao Ando

Kurayoshi Park Square in Kurayoshi, Tottori, Built in 2001, Design by César Pelli

The need to rebuild Japan after World War II proved a great stimulus to Japanese architecture, and within a short time, the cities were functioning again. However, the new cities that came to replace the old ones came to look very different. The current look of Japanese cities is the result of and a contributor to 20th and 21st century architectural attitudes. With the introduction of Western building techniques, materials, and styles into Meiji Japan, new steel and concrete structures were built in strong contrast to traditional styles. Like most places, there is a great gap between the appearance of the majority of buildings (generally residences and small businesses) and of landmark buildings. After World War II, the majority of buildings ceased to be built of wood (which is easily flammable in the case of earthquakes and bombing raids), and instead were internally constructed of steel. (Low-rise residential structures, however, are still constructed primarily of wood.) High visibility landmark buildings also changed. Whereas major pre-war buildings, such as the Wako, Tokyo Station, Akasaka Palace, and the Bank of Japan were designed along European classical lines, post-war buildings adopted the “unadorned box” style. Because of earthquakes, bombings, and later redevelopment, and also because of Japan’s rapid economic growth from the 1950s until the 1980s, most of the architecture to be found in the cities are from that period, which was the height of BrutalistModern architecture generally.

However, since around the early 1990s, the situation has slowly started to change. The 1991 completion of the postmodernist Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building was perhaps a tipping point in skyscraper design. Hot on its heels was the Yokohama Landmark Tower. In 1996 came the much-loved Tokyo International Forum, which besides a unique design, sported a landscaped area outside for people to relax and chat. More recently, in 2003, Roppongi Hills was opened, which borrowed ideas from previous ground-breaking designs and furthered them. The new area of Shiodome, completely redeveloped since the late 1990s, is an excellent place to see a group of postmodern and European-style buildings, away from the usual jumble of ’60s-era anonymous rectangular prisms. Still, despite this slow but continuing trend in contemporary Japanese architecture, the vast majority of suburban areas still exhibit cheap, uninspired designs.

The best-known Japanese architect is Kenzo Tange, whose National Gymnasiums (1964) for the Tokyo Olympics emphasizing the contrast and blending of pillars and walls, and with sweeping roofs reminiscent of the tomoe (an ancient whorl-shaped heraldic symbol) are dramatic statements of form and movement.

Japan played some role in modern skyscraper design, because of its long familiarity with the cantilever principle to support the weight of heavy tiled temple roofs. Frank Lloyd Wright was strongly influenced by Japanese spatial arrangements and the concept of interpenetrating exterior and interior space, long achieved in Japan by opening up walls made of sliding doors. In the late twentieth century, however, only in domestic and religious architecture was Japanese style commonly employed. Cities sprouted modern skyscrapers, epitomized by Tokyo‘s crowded skyline, reflecting a total assimilation and transformation of modern Western forms.

The widespread urban planning and reconstruction necessitated by the devastation of World War II produced such major architects as Maekawa Kunio and Kenzo Tange. Maekawa, a student of world-famous architect Le Corbusier, produced thoroughly international, functional modern works. Tange, who worked at first for Maekawa, supported this concept early on, but later fell in line with postmodernism, culminating in projects such as the aforementioned Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building and the Fuji TV Building. Both architects were notable for infusing Japanese aesthetic ideas into starkly contemporary buildings, returning to the spatial concepts and modular proportions of tatami (woven mats), using textures to enliven the ubiquitous ferroconcrete and steel, and integrating gardens and sculpture into their designs. Tange used the cantilever principle in a pillar and beam system reminiscent of ancient imperial palaces; the pillar—a hallmark of Japanese traditional monumental timber construction—became fundamental to his designs. Fumihiko Maki advanced new city planning ideas based on the principle of layering or cocooning around an inner space (oku), a Japanese spatial concept that was adapted to urban needs. He also advocated the use of empty or open spaces (ma), a Japanese aesthetic principle reflecting Buddhist spatial ideas. Another quintessentially Japanese aesthetic concept was a basis for Maki designs, which focused on openings onto intimate garden views at ground level while cutting off sometimes-ugly skylines. A dominant 1970s architectural concept, the “metabolism” of convertibility, provided for changing the functions of parts of buildings according to use, and remains influential.

A major architect of the 1970s and 1980s was Isozaki Arata, originally a student and associate of Tange’s, who also based his style on the Le Corbusier tradition and then turned his attention toward the further exploration of geometric shapes and cubic silhouettes. He synthesized Western high-technology building concepts with peculiarly Japanese spatial, functional, and decorative ideas to create a modern Japanese style. Isozaki’s predilection for the cubic grid and trabeated pergola in largescale architecture, for the semicircular vault in domestic-scale buildings, and for extended barrel vaulting in low, elongated buildings led to a number of striking variations. New Wave architects of the 1980s were influenced by his designs, either pushing to extend his balanced style, often into mannerism, or reacting against them.

A number of avant-garde experimental groups were encompassed in the New Wave of the late 1970s and the 1980s. They reexamined and modified the formal geometric structural ideas ofmodernism by introducing metaphysical concepts, producing some startling fantasy effects in architectural design. In contrast to these innovators, the experimental poetic minimalism ofTadao Ando embodied the postmodernist concerns for a more balanced, humanistic approach than that of structural modernism‘s rigid formulations. Ando’s buildings provided a variety of light sources, including extensive use of glass bricks and opening up spaces to the outside air. He adapted the inner courtyards of traditional Osaka houses to new urban architecture, using open stairways and bridges to lessen the sealed atmosphere of the standard city dwelling. His ideas became ubiquitous in the 1980s, when buildings were commonly planned around open courtyards or plazas, often with stepped and terraced spaces, pedestrian walkways, or bridges connecting building complexes. In 1989 Ando became the third Japanese to receive France’s prix de l’académie d’architecture, an indication of the international strength of the major Japanese architects, all of whom produced important structures abroad during the 1980s. Japanese architects were not only skilled practitioners in the modern idiom but also enriched postmodern designs worldwide with innovative spatial perceptions, subtle surface texturing, unusual use of industrial materials, and a developed awareness of ecological and topographical problems.

The Japanese asset price bubble of the late 1980s fostered a great deal of innovative and experimental architecture, but following the economic crash in the early 1990s, Japanese architecture has tended toward more minimal and humble approaches. This is exemplified by the work of architects such as Kazuyo Sejima and Atelier Bow-Wow.